|

|

|

SANDING

TEST |

|

Conducted by Nick Engler,

October 24, 2007 |

|

|

In the beginning... |

When I first learned to prepare a wooden surface with a

finish, I was told to "sand with the grain." Sanding across the grain, my

father explained to me, "left scratches" that ruined the finish beyond

all redemption. This, he impressed on me, was one of the unassailable axioms

of woodworking, a principle upon which the whole craft turned. To sand

across the grain was a sin against craftsmanship so hideous that I would be

grounded for weeks, have my allowance suspended, and made to eat

green vegetables at every meal should I even think about wiping a piece of

sandpaper across the wood at a slight angle to the grain direction.

Some years later, I bought an orbital pad sander. I

left the Church of the One True Sanding Direction and was cast out to orbit

randomly for all eternity. Or so I thought. |

|

Wandering in the desert... |

Over the intervening years, I have tested many power

sanding tools. Like so many of us, I consider sanding a singularly

dull but nonetheless important chore. After all it's the finish that people

first notice when they inspect your woodworking, and a good finish starts

with good surface preparation. So I eagerly test every sanding gizmo that

comes my way hoping that here at last is the "elegant solution" -- the tool

that will reduce the time and effort I spend sanding yet still properly

prepare the wood surface for an attractive finish.

I have explored pad sanders, disc sanders, detail

sanders, and orbital sanders as finishing sanders. Some of them work quite

well; I have had particular luck with some of the high-quality random-orbit

sanders. These machines have a little dumbbell that jerks the disc this way

and that as it turns so it doesn't leave noticeable swirls marks.

That is, it doesn't leave marks that you can see with the unaided eye. The

abrasive still travels across the grain for part of its orbit and something

has always has always nagged at my craftsman's conscious that it was leaving

scratches somewhere. |

|

The prodigal son returns... |

Recently, I was asked to test Bob Raffo's Sand Flee,

a remarkably straightforward tool consisting of a long sanding drum, a

flat table, a steel cabinet, and very little else. Because of its

simplicity, I was skeptical that it would do what he said it would do and

was surprised to find that it did. (With one exception -- it does not make

sanding "fun." Tolerable, perhaps. Fun, no.) I also couldn't help but notice

that this tool sands with the wood grain as long as you feed the work

parallel to the grain direction. Could it be that the Sand Flee does

a better job of preparing the surface for a finish than more traditional

finishing sanders? Is it possible that it leaves no cross-grain scratches,

noticeable or otherwise? I decided to perform a

test. |

|

Testing an hypothesis... |

I selected six common wood species -- oak, walnut,

cherry, maple, mahogany, and spruce. I planed these woods on a reasonably

sharp Shopsmith Pro Planer and took microphotographs at 16x of the planed

wood surfaces. Then I sanded them with a random-orbit sander, working my way

up through 100-grit, 120-grit, and 150-grit. I took another set of

microphotographs of the same area of each wood under the same lighting that

I had used before. I planed and sanded the wood

again, using the same grits but a different sanding tool -- the

Sand Flee. I took another set of photomicrographs, once again taking

pictures of the same areas of each wood under the very same lighting

conditions as before. All of the abrasives were new and had never been

used to sand before this test.

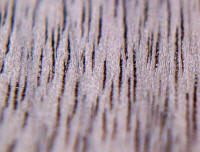

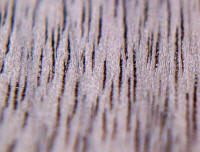

Here are the microphotographs side by side so you can

compare the results. The photos are shot at an oblique angle with the light

washing across the grain from left to right. This makes it easier to see

surface defects, but the top and the bottom areas of the photos are out of

focus. Concentrate on the center area of each photo -- this is where you'll

be able to see the most detail. Double-click of the thumbnails to

enlarge each photo. |

|

Oak, 16x |

Oak, planed |

Oak, sanded

to 150# on random-orbit sander |

Oak, sanded

to 150# on Sand Flee |

|

Walnut, 16x |

Walnut,

planed |

Walnut,

sanded to 150# on random-orbit

sander |

Walnut,

sanded to 150# on Sand Flee |

|

Cherry, 16x |

Cherry, planed |

Cherry,

sanded to 150# on random-orbit sander |

Cherry,

sanded to 150# on Sand Flee |

|

Maple, 16x |

Maple, planed |

Maple,

sanded to 150# on random-orbit sander |

Maple,

sanded to 150# on Sand Flee |

|

Mahogany, 16x |

Mahogany, planed |

Mahogany,

sanded to 150# on random-orbit sander |

Mahogany,

sanded to 150# on Sand Flee |

|

Spruce, 16x |

Spruce, planed |

Spruce,

sanded to 150# on random-orbit sander |

Spruce,

sanded to 150# on Sand Flee |

|

Observations |

Each of the sanded surfaces are comparable in smoothness,

as you would expect when wood has been sanded to the same grit. But there

are scratches across the grain in each of the surfaces that were sanded by a

random-orbit sander. In some species, notably the softer woods, these

scratches are quite prominent and easily discerned. On the harder, more

dense woods they are less noticeable. But they are there nonetheless, while

none of the surfaces of sanded on the Sand Flee show cross-grain

scratches. Please note that I did not survey any

of the random-orbit-sanded boards for areas that showed scratches, nor did I

look for clear areas on the Sand Flee-sanded surfaces. I

photographed the same general area on each board. Some of the grain

patterns do not match across the rows for the simple reason that I could not

entirely control where the microscope camera focused on each board. Each row shows

areas of a board that are separated by no more than a few millimeters, but

at this magnification (16x), a shift in focus of a single millimeter is

enough to present a different grain pattern from one photo to the next. |

|

Conclusions |

The Sand Flee produces a qualitatively better

surface with fewer severed wood fibers than does the random-orbit sander

used for this test (Porter Cable Model 7336). This is most probably due to

the fact that the Sand Flee abraded the wood in the same general

direction as the wood grain, with the grit "combing" the fibers. With the

random-orbit sander, the abrasives sometimes traveled at an angle to the

fibers, cutting them and leaving marks that appear as scratches. |